EMV Technology

What you need to know:

EMVEMV stands for Europay, Mastercard and Visa, and is technology introduced by these operators and governed by EMVCo. The chip technology uses encrypted dynamic information embedded on a microchip processor for payment transactions at point of sale locations. technology is an important security tool, but it only protects against one kind of fraud. It does not protect against card data breaches, just the misuse of stolen card information. Much more needs to be done to enhance card security in the United States.

EMV is a technology introduced by EuroPay, Mastercard, and Visa. EMV technology stores and encrypts payment card credentials on an embedded microprocessor chip, which uses encrypted dynamic information that is used for payment transactions at point-of-sale locations. EMV chip technology only protects you against Card Present (CP) When a credit or debit card is present for payment at a brick and mortar merchant location. counterfeit fraud that occurs at brick-and-mortar retail locations. It does not protect against eCommerce fraud or lost and stolen card fraud.

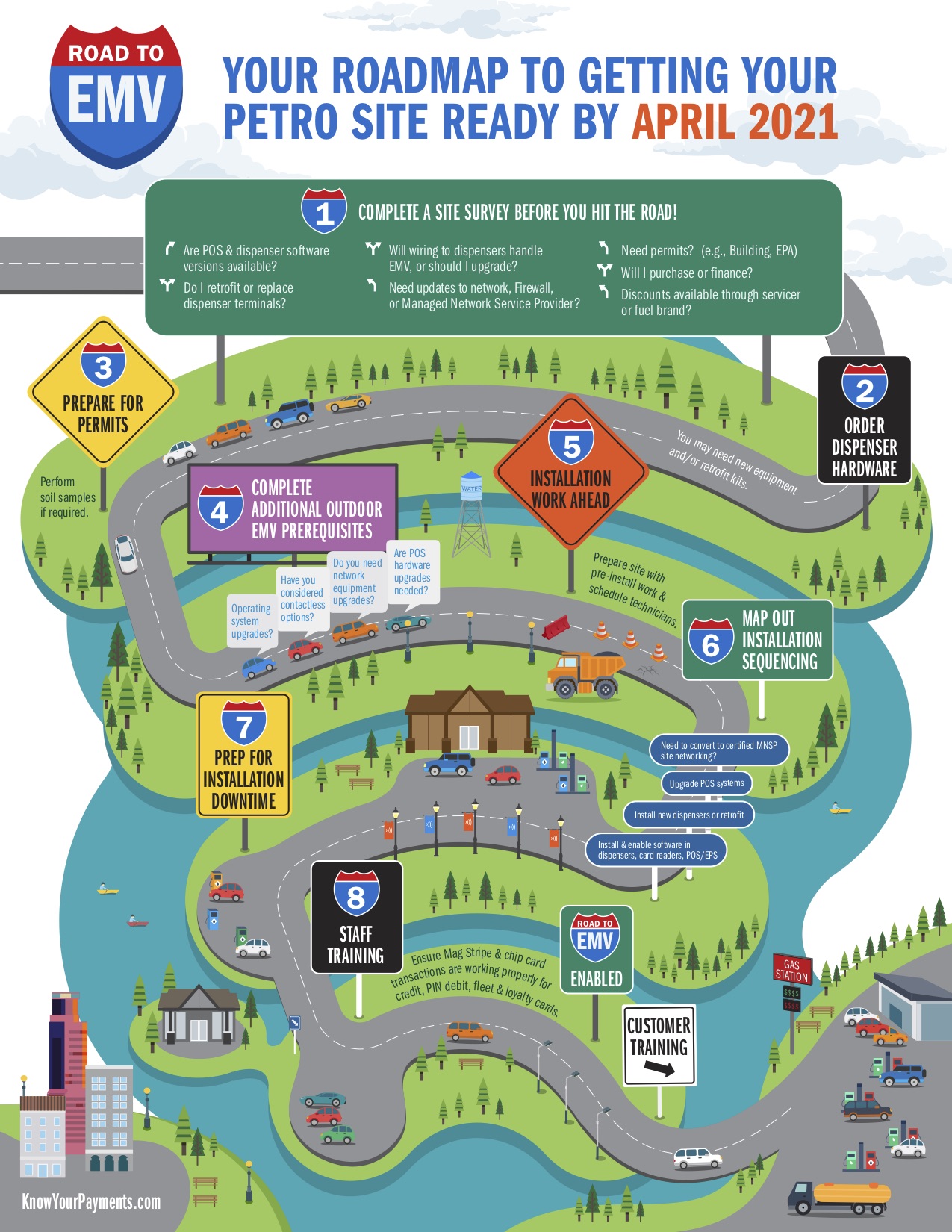

In October 2015, brick-and-mortar retailers faced an EMV liability shift for CP transactions; and in April 2021, fuel merchants will see a liability shift at Automated Fuel Dispensers (AFDs).

History of Chip-and-PIN

As credit cards and debit cards began to overtake cash in terms of payment popularity, the need for more secure payments was evident. By the early 1990s, the Magnetic stripe (magstripe)The stripe on the back of credit and debit cards that holds important account information including: cardholder name, zip code, CVV number (different from the one printed on the card) and account number and signature During a payment transaction, when a card is swiped, dipped or tapped and a signature is captured as a customer verification method. were no longer the most secure option, so a card with a microchip was developed and chip-and-pin EMV cards were rolled out in Europe. These debit and credit cards were enabled with PINs the same as ATM and magnetic stripe debit cards in the United States.

The U.S. has been much slower to adopt chip card technology. According to Consumer Reports, the United States has been excessively slow in mandating chip-and-pin technology, stating “So why is the U.S. so far behind? It seems to come down to money. The losses for banks do not yet exceed the costs of a switch-over, although merchants say that’s because they usually shoulder much of the cost burden from fraud.”

“In much of the world, as an anti-fraud measure, cardholders enter a PIN when using credit cards. Almost all United States credit cards, in contrast, are not configured with PINs.”

Even so, the U.S. finally began the migration to EMV as outlined by Visa and other global credit card brands in late 2011/early 2012. Under that roadmap, as of October 1, 2015, credit card networks began shifting counterfeit card fraud liability toward the party – between the issuer and the merchant – with the least capable support of chip technology. Prior to October 1, 2015, counterfeit card-present fraud was borne by the banks.

Dating back multiple years, United States merchants called for an implementation of the international version of chip-and-PIN technology but have been forced to settle for the current iteration set by the signature networks, which in most cases leverage signature authentication over more secure PIN technology.

Consumers who have chip cards without a PIN or another second layer of security have antiquated technology, like when smartphones could not be PIN-locked. According to WIRED, chip cards won’t stop card fraud altogether since the history of hacker ingenuity shows that when one method is blocked, hackers simply shift their focus and find another. The EMV cards also have magnetic stripes that can be used most places.

One of the largest concerns with EMV is that it is a closed specification, with Visa, Mastercard, and a few other global networks controlling the technical specifications and implementations, making it more difficult for merchants and other partners in the payments ecosystem to weigh in on important aspects of the technology. The closed nature of EMV technology could have long-term negative impacts for both businesses, as well as consumers. The way the chip technology works disadvantages domestic United States card networks.

Financial institutions need to be leaders in ensuring cardholder authentication mechanisms – PINs or otherwise – are enabled on financial products so that merchants have the choice to ask for PINs on high-dollar, high-risk transactions. And the U.S. needs to continue to deploy broader security technologies, like end-to-end encryption and tokenization services, to better protect payment card data at rest, as well as when it moves through the transaction process.

Since EMV technology only protects against one kind of fraud, in-store counterfeit fraud, it is not the end-all solution.

FAQ

What were the EMV liability shift deadlines?

Brick-and-mortar retailers faced an EMV liability shift in October 2015. Fuel merchants were given additional time to implement EMV at the AFD and, as a result, the liability shift deadline was April 2021.

What does the EMV liability shift deadline mean?

There is a common misbelief that on the liability shift date most merchants were required to have EMV-equipped point-of-sale payment devices. This deadline means that there was a fraud-liability switch to the party least EMV enabled. Visa was first to announce an EMV deployment liability shift date of October 1, 2015, for general retail, and the other global card brands issued similar timelines and roadmaps for transition shortly thereafter.

Card Issuer Liability:

If a retailer has installed and activated EMV card reader equipment, and the customer presents a non-chip magnetic stripe card at checkout, the card issuer is responsible if fraud occurs.

Merchant Liability:

If a customer presents a chip card where an EMV terminal is installed, but not activated, the retailer is responsible in the case of fraud on that transaction.

How does EMV make my payment more secure?

EMV technology partially solves the counterfeiting of today’s current system of magnetic stripes. Account credentials and some limited cardholder information are stored on both the magstripe and chip including cardholder name, address, zip code, card number, CVV (different from the CVV2 on the back of the card), and expiration date.

“The United States is finally catching up with the rest of the industrialized world by deploying more secure chip card technology.”

The main difference between the chip and magnetic stripe is the CVV number in chip transactions uses a dynamic value each time that is unique to the transaction, instead of using a traditional static value. The information on the chip is also stored more securely than the magstripe making it more difficult to steal and re-create a counterfeit card.

Is the EMV technology in the U.S. the same as abroad?

In much of the world, as an anti-fraud measure, cardholders enter a PIN A personal identification number which is unique to the card and known only to the cardholder. It is entered when a card is swiped or dipped into a card reader. when using credit cards. Almost all U.S. credit cards, in contrast, are not configured with PINs. Even as U.S. banks replace traditional magnetic stripe cards with EMV chip cards, they are choosing not to offer PINs and instead seek to verify a transaction with a customer’s signature.

As Chip and signature becomes more widely accepted and adopted in the United States for credit cards, this will create some challenges for U.S. cardholders trying to use EMV products in Europe and other countries where cardholders are required to enter a PIN. This has caused problems for Americans trying to use their credit cards overseas, especially at unattended payment terminals like parking meters or train station kiosks. Often the kiosks ask for a PIN. If you weren’t issued one on a credit card, the machine may not process the transaction and there is no clerk available to help override the PIN acceptance requirement for international cardholders.

How does my chip card work at the point-of-sale (POS)?”

The computer application on the chip talks to the terminal at the merchant POSIn a brick and mortar store the location where payment transactions for goods and services take place. This can also be the payment screen for an eCommerce or mCommerce sale. In such instances POS and POI – point of interaction – are used interchangeably. This requires significant programming by the merchant and their acquirerA bank or financial services company, that has a relationship with the merchant, that processes the credit or debit card payment. (a bank or financial services company that processes the credit or debit card payment), as well as software and hardware providers and other payments transactions stakeholders. The capability to do an EMV-like contactless transaction, through mobile payments such as Apple PayProprietary technology used by Apple devices to pay for goods and services in brick and mortar locations, in-app purchases, as well as in the eCommerce environment., is available in the U.S.

What does EMV mean for online transactions?

EMV has no impact on reducing fraud for internet transactions. However, counterfeit fraudWhen a criminal makes copies of a credit or debit card using illegally or fraudulently obtained data. attempts have migrated online with EMV use increasing in-store based on evidence from international market deployments of EMV. The use of counterfeit card numbers by fraudsters have moved to the online space because counterfeit cards will become more difficult to use for in-store purchases.

“EMV has no impact on reducing fraud for internet transactions.”

Larger Internet merchants will be able to evolve and adapt to these scenarios, but the smaller merchants will be the hardest hit.

If my card has a chip, why am I still swiping?

Not all merchants have been able to turn on the EMV system yet. The roll-out has been slowed because the EMV owners – Visa, Mastercard, etc. – were late in delivering technical specifications to the market. Implementation timelines were also unrealistic. Canada’s financial service market is one-tenth of the size of the U.S.’s and they had nearly 10 years to implement. The U.S. has only had four quick years to implement, and less than one year after the technology parameters were fully released. Merchants have been doing everything possible to stay on track with the accelerated timing, but the card network delays caused a ripple effect.

Merchants want the best experience for you, their customers, so once the technology is installed, ample testing and certifications must take place. Merchants will only take the technology live once they are certain all kinks are sufficiently erased, and they can ensure a good customer experience.

Additionally, some merchants have not installed the hardware yet because there were delays in getting the equipment or many of their card fraud risks are not in the CP When a credit or debit card is present for payment at a brick and mortar merchant location. space – and they want to use their resources to deploy other fraud prevention technology like tokenizationTokenization is the process of replacing one number with another unrelated number. and encryptionThe process of encoding a message so that it can be read only by the sender and the intended recipient first.

Who’s responsible for fraud loss with EMV?

Banks and merchants each have varying degrees of fraud liability.

The below graphs showcase fraud loss in the former magnetic stripe environment. With EMV, fraud will only be prevented in CP scenarios, where nearly 67 percent of all loss was borne by banks. Merchants want to have the ability to ask their customers to enter a PIN with their chip cards because the total fraud on PIN transactions is significantly lower for everyone involved.