Transaction Basics

What you need to know:

The payments ecosystem The current state of the payments infrastructure in the United States. in the U.S. is a complex environment. While the process of dip, swipe, tap, or click to pay can be a mystery to many, a large, complex set of stakeholders are responsible for a seamless transaction from beginning to end of the payment process. There are systems currently in place to protect your information and secure data, but they can be even stronger.

FAQ

What is the transaction flow?

What role do merchant acquirers/processors, networks, and bank processors play in the payments ecosystem?

A merchant is the acceptor of payments. When a consumer pays a merchant for goods and/or services, either online or in-store, the payment is initiated via a swipe, dip, tap, scan, or click. Each of these methods transmits the consumer’s card information throughout a complex environment so the merchant can ultimately be funded for the payment. This is called a pull-payment, since the merchant is effectively pulling the payment out of the consumer’s account.

Card networks also create and govern the rules a merchant must follow to accept the network’s cards.

Authorization of Payment

The merchant passes the card information to the acquirer for authorization of the payment. The acquirer then sends the authorization request to the card network associated with the card. The card network receives the authorization request and routes it to the consumer’s bank, which issued the card, for approval. It is the consumer’s bank that determines whether the authorization request should be approved or denied and passes that decision back through the same process in reverse order.

Settlement and Funding of Payment

For approved transactions, the acquirer submits a settlement request to the card network on behalf of the merchant. The card network then sends the settlement request to the consumer’s bank, which issued the card, for clearing. As part of this clearing process, the card network pulls the funds from the consumer’s bank and passes it back to the merchant’s acquirer for funding to the merchant. The merchant’s acquirer will net out any fees associated with the transaction processing prior to funding the merchant’s account. These fees include both the card network’s fees as well as the acquirer’s fees.

What role does the network play in the payments ecosystem?

Card networks play an important role in the payments ecosystem by facilitating the entire authorization, settlement and funding process between the merchant’s acquirer and the consumer’s bank. By facilitating this complex process, acquirers do not have to interact with each consumer’s bank individually.

Card networks also create and govern the rules a merchant must follow to accept the network’s cards. Card networks have the authority to penalize a merchant for not following these strict rules by imposing fines or in severe cases prohibiting acceptance of the network’s cards.

In addition to creating and governing the rules, the card networks set the fees a merchant must pay to accept the network’s cards. A large portion of these fees is what is commonly referred to as “interchange,” which is the amount card networks charge merchants to give the consumer’s bank for issuing the card.

What role does the financial institution play in the payments ecosystem?

Financial institutions, also referred to as simply the consumer’s bank, play a crucial role in the processing of payments. The consumer’s bank manages the available balance the consumer has at any given moment. The available balance along with other information received as part of the transaction is what the consumer’s bank uses when determining if the transaction should be approved or denied.

For approved transactions, the consumer’s bank allows funds to be pulled from the consumer’s account and passed to the card network. The card network passes those funds on to the merchant’s acquirer, who deposits the funds into the merchant’s account (less any transaction fees).

What data is sent in a transaction?

Merchants send payment information for each customer purchase to the network and ultimately to the bank’s processor.

Card Present Authorization

Typical data elements include merchant identifiers, method of entry, transaction total, card number, card expiry date, card CVV code, billing zip code, currency code, plus a few others. For multi-factor authenticated transactions (i.e. PIN debit), the consumer’s PIN is passed in a securely encrypted field.

For EMVEMV stands for Europay, MasterCard and Visa, and is technology introduced by these operators and governed by EMVCo. The chip technology uses encrypted dynamic information embedded on a microchip processor for payment transactions at point-of-sale locations. transactions there are additional data elements passed which include a unique identifier for each transaction to validate that the card is not counterfeit.

Card Present Settlement

Most of the data elements used in authorization are also passed in settlement, excluding CVV and PIN.

Card Not Present Authorization

Typical data elements include merchant identifiers, method of entry, transaction total, card number, card expiry date, card CVV2 code, billing zip code, currency code, plus a few others.

If a merchant is using a card network sponsored fraud mitigation tool like 3DSecure, then specific data values are passed indicating the merchant utilized the 3DSecure toolset.

Most of the data elements used in authorization are also passed in settlement, excluding CVV2.

How is a transaction authorized and settled?

When a consumer pays a merchant for goods and/or services, either online or in-store, the payment is initiated via a swipe, dip, tap, scan, or click. The merchant passes the card information to the acquirer, or merchant bank, for authorization of the payment. The acquirer then sends the authorization request to the card network associated with the card. The card network receives the authorization request and routes it to the consumer’s bank, which issued the card, for approval. It is the consumer’s bank that determines whether the authorization request should be approved or denied and passes that decision back through the same process in reverse order.

For approved transactions, the acquirer submits a settlement request to the card network on behalf of the merchant. The card network then sends the settlement request to the consumer’s bank, which issued the card, for clearing. As part of this clearing process, the card network pulls the funds from the consumer’s bank and passes it back to the merchant’s acquirer for funding to the merchant. The merchant’s acquirer will net out any fees associated with the transaction processing prior to funding the merchant’s account. These fees include both the card network’s fees as well as the acquirer’s fees. None of these fees are charged directly to cardholders but are instead charged to the merchant.

Ultimately, any fees assessed as part of the transaction whether to the merchant or the consumer’s bank are also an integral component of the prices merchants charge to all of their customers, whether the customer pays with a card or with cash.

What is the difference between a dual message and a single message transaction?

Dual-message transactions are processed in two steps. The first step involves “authorizing” the transaction by checking with the consumer’s bank to make sure funds exist in the cardholder’s account. The second step involves the periodic bundling of authorized transactions and sending them to the consumer’s bank for posting to the cardholder’s account. This process was invented in the 1960’s and is modeled after the process used to clear and settle paper checks. Most dual message transactions do not require a PIN, but instead require the customer to sign at the POS. Since signatures are not verified in real-time by the consumer’s bank that issued the card, merchants must utilize other techniques to verify that transactions are legitimate, such as fraud mitigation methods, or accepting biometrically authenticated digital wallets.

By contrast, single-message transactions require the customer to enter a PIN which is verified real-time by the consumer’s bank. PIN transactions are inherently safer and much less prone to fraud since the consumer’s bank is validating that the PIN is correct before approving the authorization request. Single-message transactions do not require a settlement file to be sent to the consumer’s bank.

What is the difference when I use my debit card if I choose debit or credit at the POS?

The major difference is the determination of whether the transaction will be “single-message” or “dual-message” and what level of authentication will be used. When you press the credit option instead of entering your PIN, it is a matter of where and how the data flows. Utilizing the PIN makes the transaction more secure, since it uses a second method of verification, the encrypted PIN, which is validated by your bank. The PIN is validated real-time, whereas the signature is not.

Fraudsters will always choose the path of least resistance in an effort to gain approval of the transaction, which is one reason signature (or credit) transactions are more fraud-prone. The major card networks that issue hybrid debit cards – cards that can be used with both a signature and a PIN – require that a merchant allow a consumer to opt out of entering a PIN, thus requiring a merchant to support a less secure method of payment.

Why don’t all merchants ask me for a PIN?

The consumer bank technology infrastructure in the U.S. to support online PIN changes is not in place at this time, which would create customer issues when changing or creating a PIN. Additionally:

- PIN acceptance requires a significant technology update for merchants, but many do it for the added security.

- Issuers do not require PINs to be added for consumer protection on all of their cards.

- Unfortunately, the EMV rules adopted in the U.S. by the card networks did not require issuers to include PIN as an option for authenticating payments.

- In some instances, merchants may not want to ask for PINs on low-dollar, low-risk, low-fraud transactions like at quick-service restaurants.

What is considered a card present (CP) vs. a card not present (CNP) transaction?

Card present (CP) When a credit or debit card is present for payment at a brick and mortar merchant location. transactions, simply put, are when you are present at a point-of-sale terminal with your card or mobile device. Card not present (CNP)When a credit or debit card is not present for the payment transaction. Most often used in the e-commerce environment. situations occur when you are not physically swiping, dipping, or tapping a card at a point-of-sale terminal, such as purchasing goods and services online or through a mobile phone application. This also includes phone-in orders. There is a big difference between CP and CNP in terms of liability and cost to merchants.

In a CNP scenario, you shouldn’t be afraid to let merchants know who you are from a security standpoint. Your IP address, and other indicators, let them know you are who you say you are, decreasing the risk of fraud.

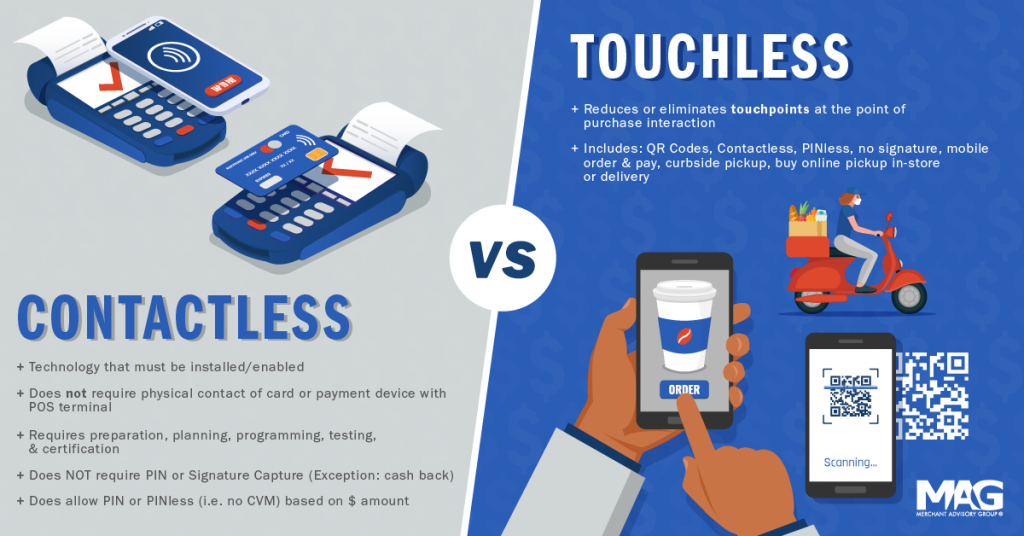

As customers’ shopping habits evolve and CNP transactions become more prevalent, merchants are seeing more contactless and touchless transactions than ever before. Understanding the difference is key for merchants as they strategize about CNP card acceptance. Learn the difference between contactless and touchless transactions in our graphic below:

How much does it cost consumers to use credit or debit cards?

Most U.S. consumers pay nothing to use a credit or debit card at merchants per transaction. Some credit card programs that offer high rewards will cost consumers an annual fee that is paid directly to the issuer. Surcharging is not a desired practice for most merchants. Even so, there are network acceptance rules that largely prohibit surcharging cards, and there are laws in 11 states that explicitly prohibit card surcharges. All consumers do indirectly pay for the fees associated with using a credit or debit card.

How much do merchants pay in credit card fees?

The biggest fee merchants pay is the interchange, or “swipe” fee, which is pre-set by Visa and Mastercard and is revenue collected by large issuers. Roughly 90% of the credit card fees in the U.S. are collected by the 10 largest U.S. banks. [See GAO pg 6].

As of 2009, there were over 300 different interchange rates ranging from 0.95% to 3.25% of the transaction according to the Government Accountability Office. Since then, credit card fees have only continued to grow, and are perpetually one of the top three highest operating costs for most merchants. The estimated average interchange fee for small restaurant operators is 4.36% of every sale [See USA Today.]

Merchants also pay credit card fees to their acquirers and processors, as well as network fees directly to Visa and Mastercard.

Why do some merchants ask for a minimum transaction amount for using a credit card?

Prior to Dodd-FrankA federal law passed in 2010 which provided significant changes to financial regulation in the United States, including debit card reforms., merchants set minimum credit transaction amounts at their own risk. Visa and Mastercard network acceptance rules allowed the card networks to fine those merchants starting at $5,000 per day for setting minimums on cards. The cost of taking cards has grown so high merchants are simply trying to protect themselves from high costs by asking their customers to pay with cash or cheaper forms of payment on small-dollar sales.

Dodd-Frank protected merchants’ ability to set minimums on credit cards not to exceed $10, but it does not provide the same protections for debit likely due to concerns over accessibility to pre-loaded consumer funds.

How much do merchants pay in debit card fees?

According to 2021 Federal Reserve data, merchants pay $31.59 billion in debit card interchange swipe fees along with $7.34 billion in network fees on debit transactions totaling $39 billion. Merchants also pay processing costs for debit card acceptance, which are negotiated with the merchant’s acquirer/processor. Banks also pay $4.15 billion in network fees.

Debit interchange swipe fees are regulated for issuers of four-party (Visa and Mastercard) debit cards who 1) have over $10 billion in assets, and 2) refuse to negotiate free market interchange swipe fee costs directly with merchants. According to Federal Reserve data [same link], the average interchange fee on regulated debit transactions was 23 cents in 2021, while the average technology cost of processing these transactions was 3.9 cents. The average debit interchange rate on unregulated debit transactions is 50 cents.

What is an interchange fee?

Every time a customer swipes or dips a credit or debit card at a merchant or enters card details online, that business pays an interchange fee to their merchant acquirer/processor who then passes through the interchange fee revenue to the card-issuing bank (i.e., Bank of America). In addition to interchange fees, the merchant pays network fees to Visa and Mastercard and processing fees to their merchant acquirer/processor (i.e. Fiserv) that constitute the total cost of accepting credit and debit cards.

How are interchange swipe fees set?

Interchange fees are set by card networks. When a bank issues a credit or debit card, it generally has a Visa or MasterCard logo on the front, and possibly a handful of other PIN debit network marks (i.e., Star, Pulse, NYCE) on the back. Any time a cardholder uses their card, the issuer gets interchange fee revenue at the level set by the network for that transaction, so it is in the best interest of the networks to keep raising interchange fee rates to drive more revenue to the issuers and in turn get their network marks on more cards. There are some serious competition issues surrounding whether networks should be allowed to set interchange fees for the banks.

A Federal Reserve economist explained interchange in this way:

“As you know, in most markets increased competition leads to lower prices. However, in payment card markets, competition between networks tends to drive interchange fees higher.”

Federal Reserve Board of Governors Open Meeting December 16, 2010.

Why do some businesses pre-authorize funds (like hotels, restaurants, gas stations)?

This is specifically to ensure sufficient funds are available in the account that the card is linked to by authorizing an electronic transaction with a debit card or credit card and holding this balance as unavailable either until the merchant settles the account, or the hold falls off.

When a merchant swipes a customer’s credit card, the point-of-sale connects to the merchant’s acquirer, or credit card processor, which verifies that the customer’s account is valid and that sufficient funds are available to cover the transaction’s cost. At this step, the funds are “held” and deducted from the customer’s account but are not yet transferred to the merchant. This is a common practice where the amount being authorized at the swipe may differ from the total charge amount, such as when a customer adds a tip at a table-service restaurant or when a customer uses their card to turn on a gas pump without the final sale total being known.

What are private label cards and how do they work?

For private label cards (e.g., Macy’s, Kohls, etc.) there are three primary entities – the consumer, the merchant, and the issuer. In the case of a private label card, the merchant knows the consumer due to the direct relationship between consumer and merchant brand. The issuer serves as the processor/acquirer and can look at the consumer’s information at a granular level, including the ability to look at what they are purchasing, and thus are able to identify fraud and risk more easily.

What are co-branded cards and how do they work?

Co-branded cards are usually credit cards that involve a partnership between a merchant and a card network. These cards work like credit and debit cards and can be used at several merchants, not just the merchant with which the card is branded. Co-branded cards are most prevalent in the airline and hotel industries, but the strong business case and growth of rewards have led to the emergence of cobrand programs in other industries, such as big box retail.

How do my network-branded (i.e., Visa and Mastercard) gift cards work?

Gift cards that can be used at a variety of different retailers are called open-loop or network-branded gift cards. These cards work similar to credit and debit cards.

Why can’t I use the full amount of my network gift card everywhere in one swipe?

The default setting for most merchants and payment systems would be to pre-authorizeA set amount of money is held on a credit or debit card to cover the likely final charges. Mostly used at gas stations, hotels and restaurants. a specific amount of money for a transaction, and sometimes this accounts for more than the amount available on the card – such as at a gas pump, hotel or restaurant. If this is the case, the card may be declined. For example, in restaurants, the amount will automatically pre-authorize for a 20% tip to ensure funds are available for a consumer to add that tip. This is an antiquated process that will hopefully be resolved with mobile commerce and faster payments.

How do retail gift card programs work?

Retail gift cards are usually available for redemption at a specific retailer, or a few retail brands owned by the same parent company. The technology to transact is safer and more secure through closed-loop gift cards. These programs can also be very low cost in terms of transaction fees.

How do Electronic Benefit Transactions (EBT) work?

The primary EBT program in the US is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps. SNAP EBT has very low fraud rates in part because they require PINs on every transaction.

Essentially, while unknown to them, people on benefit programs are subsidizing Visa, Mastercard, and large banks because paying for the costs of transaction fees is built into the cost of all products.

“Do the ‘Honor All Cards’ rules apply to a brand’s debit and credit cards?

The Honor All Cards rules (and now, the Honor All Wallets rules) do not cross between credit and debit products but do apply to all cards issued within those product types. Therefore, if a merchant accepts one branded credit card, they must accept all of that brand’s credit cards. Similarly, if the merchant accepts one branded debit card, they must accept all of that brand’s debit cards. Litigation in the mid-1990s enabled a merchant to accept a brand’s debit products while not requiring the acceptance of the same brand’s credit cards and vice versa.